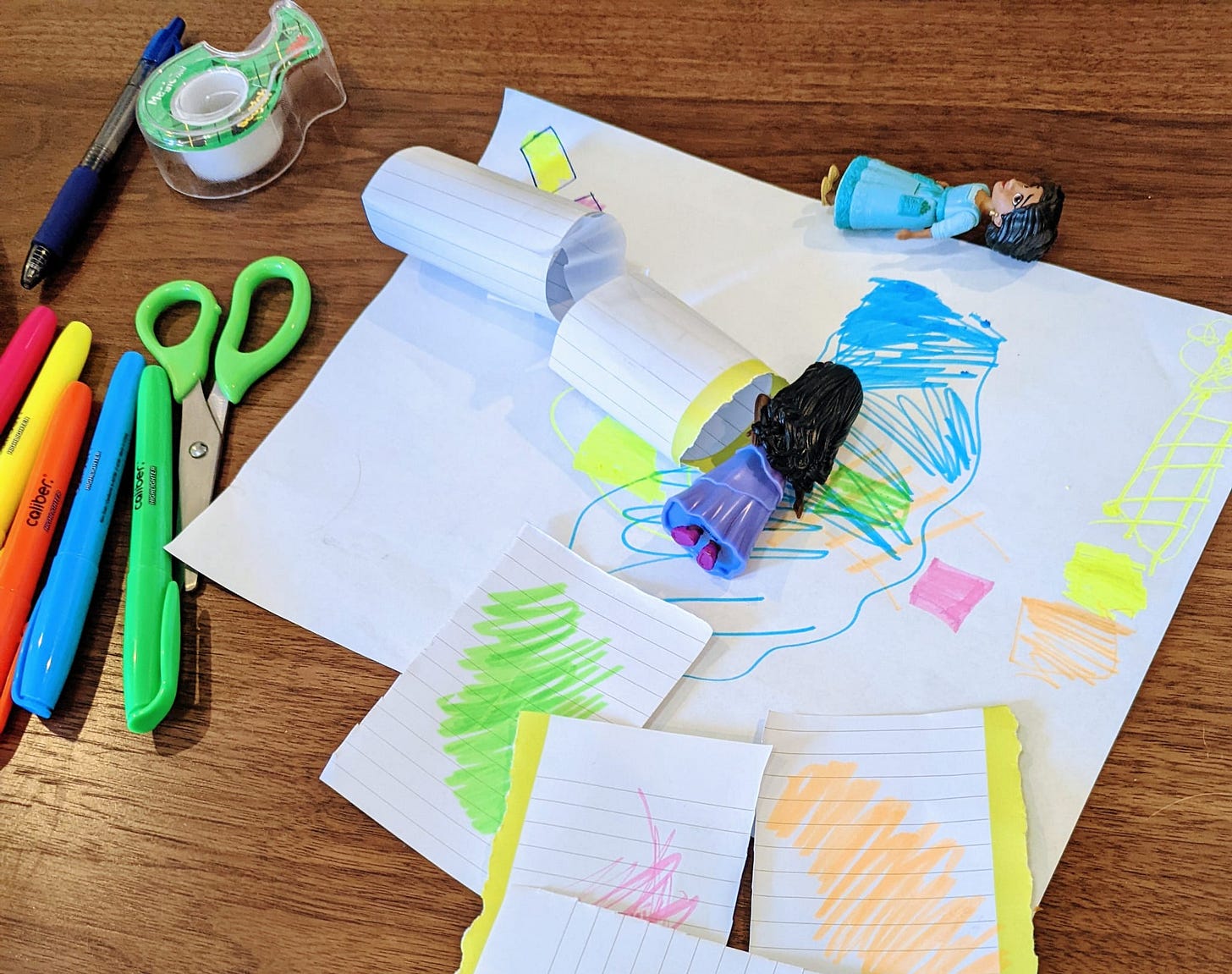

Today I created a board game with the kiddo.

She came home from school having drawn a detailed mock-up. “We have to help the ducklings get to the tree,” she said, and pointed out a river, a bridge, a log. The obstacles between here and there.

She asked if we could build the game, and I remembered my own board game at a similar age, how I colored the little pieces and glued squares on the board and sent a prototype to the kids’ show Zoom (that’s “Z-double-O-M, Box 3-5-0, Boston, Mass 0-2-1-3-4”).

This project lit her up in the same way. I could tell she had been thinking all day about what we had to do, how to achieve the vision in her head. “Okay,” she said. “So. We need a log. And game pieces. And a bridge.” We gathered supplies, riffed on different iterations for each component.

I asked her where she had come up with the idea; she said it came from a video she’d seen on her iPad.

That’s not unusual. She watches a new episode of My Little Pony, and the next time we play, she’s directing me in a scene pulled straight from Netflix. She feeds me the correct dialogue; she demonstrates the blocking; she even stops me mid-scene and tells me to start over if we’re missing the right energy.

Apparently reenactment and mimicry is a huge part of pretend play for children. Adults might think that make-believe consists of purely original invention, but the truth is that make-believe is how kids process events and observations from daily life. They learn by imitating what they see.

It strikes me that any kind of storytelling or creative work is not so different from a child’s make-believe. We might strive to create an original piece of art, to write a story that hasn’t been told yet—but the truth is, it’s all been done before.

A compelling story is one that helps us process some truth in life. The story might accomplish that task in a new way, from a new approach or angle, but the question or meaning at the root is never wholly original.

I suppose some creatives might find that thought discouraging. What’s the point, if we can’t expect to achieve pure originality?

But what if we choose to feel reassured instead? What if acknowledging this means that a burden is lifted; that it’s not our responsibility to create something from nothing but rather to mimic what we see? To reflect on and process the reality we experience instead of inventing another reality?